THE LAY OF THE LAND

An Ansel Adams Sampler, 1927-1958

By Colin Westerbeck

The subject of Ansel Adams’ best known photography is, of course, the drama of America’s western landscape. Yet in his old age, Adams himself became an even bigger subject. He turned into a mythic figure whose fame almost eclipsed the work on which it was based. Even his death in 1984 didn’t diminish the focus on him as much as, or even more than, his photography. It seems that you still can’t get back to the photography unless you first deal with—or maybe dispose of—the legend of the man. When you look at what Adams and others have said about his pictures, as well as at the pictures themselves, you realize that he had to straddle two eras in the history of art. He needed the equilibrium to be both a dyed-in-the-wool Romantic and a struggling proto-Modernist at the same time. His ability to juggle with these two irreconcilable aesthetics was what made Adams a great photographer.

In the early chapters of Ansel Adams: An Autobiography, published in 1985, Adams lives a life that could have inspired Booth Tarkington’s novel Penrod. He bests a school-yard bully by hitting him with a round-house punch that knocks the miscreant out cold. And when the 1906 San Francisco earthquake turns his family out of their house, he helps the cook set up a stove in the front yard so everyone can have breakfast. When he tells us in the autobiography that “my childhood was very much the father of the man I became,” he is adapting “the child is father of the man,” an observation made originally in 1802 by that most Romantic of all English poets, William Wordsworth. The poem in which the line occurs begins with a sentiment by which Adams might have been inspired as well: “My heart leaps up when I behold/ A rainbow in the sky.”

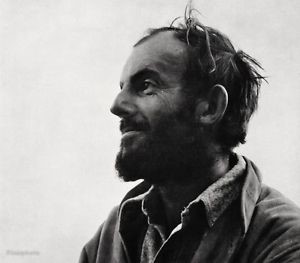

In a portrait made in the 1930s, photographer Cedric Wright looked up at Adams as Adams himself looked up as though he were scanning the sky for some higher truth. His gaze into nature was in effect a Romantic vision of a particularly American sort. It was the Transcendentalist vision described by Ralph Waldo Emerson as an all-seeing eye gazing into Nature (with a capital N). However, unlike Emerson, who was inspired by the more accommodating, eye-level world of New England, Adams’ was born into the Big Sky country of the West whose scale and vastness demanded a larger vision.

While In Focus: Ansel Adams Highlights from Lawrence Janss Collection is a small sample of Adams’ work, the exhibition has been thoughtfully put together in a way that affords insights into Adams’ talent in general. The earliest print in the exhibition, “Monolith”, 1927, represents a moment of discovery for what would become the signature style of Adams’ landscape photography. “I saw the photograph as a brooding form,” he recalled later, “with . . . a distant sharp white peak against a dark sky.” To get the effect he wanted in the sky, he used his “deep red Wratten No. 29 filter.” Thus did he originate the dark skies and backgrounds characteristic of later prints in his oeuvre.

The one photograph in the show not by Adams – Timothy O’Sullivan’s “White House Ruins,” 1873 – throws into instructive relief the Adams view of the same subject. O’Sullivan had been a photographer documenting the unprecedented slaughter of the Civil War, after which he took on a subject even more unprecedented: government-sponsored US Geological Survey trips along the 40th Parallel and the 100th Meridian mapping the terra incognita of the American West. O’Sullivan’s photograph of the “White House” pueblo in Canyon de Chelly was made on a later government-sponsored survey. Adams also photographed in Canyon de Chelly on at least three occasions: first in 1941, then on a return trip in 1942, and again in 1949. The first study, “White House Ruins,” 1941, is the one in this exhibition. On the second trip the next year he photographed the same subject from a different perspective, and on the third trip he moved to a different site but one with a similar subject, “Antelope House Ruin.”

Even though the 1941 trip was his initial encounter with the White House site, Adams felt that this subject was terribly familiar despite his never having been there before. The reason for this déjà vu, he later realized, was that many years earlier a friend had given him an album of O’Sullivan’s photographs published by the government in 1874. In it was O’Sullivan’s own, 1873 photograph of the pueblo. Like the skies in many Adams photographs, the vertical striation of the cliff face caused by water run-off is preternaturally dark – much darker than in O’Sullivan’s image. Otherwise, though, especially in the position from which he photographed the pueblo, Adams’ composition is almost exactly the same as O’Sullivan’s done 68 years earlier. In both men’s interpretation, the wall of rock is enormous as it bears down on the tiny buildings below.

Yet another image by Adams that bears comparison to this one is “Moonrise,” which was also made in 1941 and is also composed of a tiny human settlement beneath a massive natural phenomenon. This became the most famous, often reproduced photograph Adams ever made. Yet it was composed and executed in a state of near panic. From the time he spotted this subject while driving past Hernandez, New Mexico, he had only a few minutes until the effect that had inspired the image – the last rays of sun glinting off the crosses in the cemetery – would fade into night. Again, a Wratten filter was crucial to the exposure, which he had to guess at because in his rush to set up the camera he couldn’t find his exposure meter. Realizing that he did know the luminance of the moon,he used that to set the exposure for the one shot he got off before the graveyard went dark. The result was the hardest negative he ever had to print, but also the one that gave him the most popular response an image of his ever received.

By contrast, Adams’ 1945 photograph of “Mount Williamson from Manzanar,” capped off the most controversial photographic adventure of his career. The image was made, as its caption acknowledges, from the Manzanar relocation camp where Japanese Americans were interned in the California desert during World War II. The very concrete subject of the rubble from a mountain destroyed by time sits in the image’s foreground, while beyond it is Mount Williamson, a mirage wrapped in a vapor of clouds and rays from the sun. The image could be seen as one symbolic of a culture lost in time whose remnants are now scattered on the desert floor, as were Japanese-Americans at Manzanar. While trying to show the resilience of the displaced Japanese in his book Born Free and Equal, Adams created a photographic record that made what had happened to them seem like a triumph rather than the injustice that it was. “Ansel just doesn’t get it,” said Dorothea Lange, who had made a photographic record of the Japanese being displaced from their homes and loaded into trucks. At that point, their dispossession and forced removal to concentration camps looked more like what was happening to the Jews in Germany.

It’s not surprising that in a career of many decades and wide-ranging subjects, Adams would come in for some controversy along with the accolades. As the former fades with time, the latter remain fresh because Adams’ aesthetic and stylistic innovations are still important to the history of photography. For me it is the proto-Modernist, more than the retro-Romantic, that makes Adams one of the premiere photographers of the 20th century. There is a kind of subconscious, subversive formalism to his photography, an abstract graphic patterning that dramatizes his subjects while remaining strictly implicit so that it doesn’t distract the viewer or detract from the subject. One notices what I am calling his ‘formalism’ only when comparing one or more subjects that he photographed to similar effect.

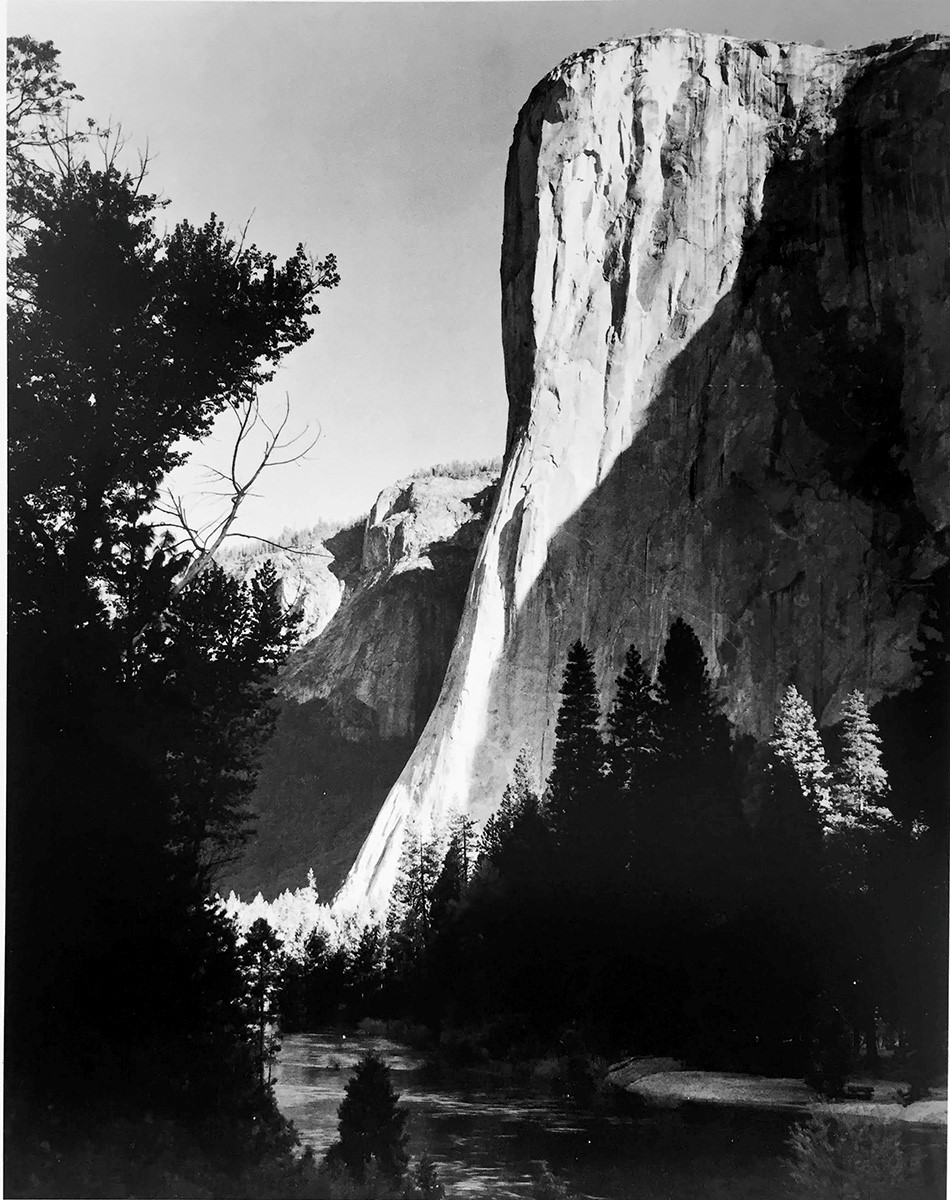

Look, for instance, at these three photographs made in different years and at different seasons. Two of them are in the exhibition, while the third, undated one is drawn from a 1960 Adams portfolio titled The Yosemite Valley. Notice how the same graphic effect is created in all three through a combination of shadows and seasonal atmospheric conditions.

In the two of El Capitan, Adams has characteristically chosen a point of view that shows the rock face in profile rather than head-on, as it is more typically seen in photographs. Despite being made at opposite times of the year, the two studies of El Capitan are very close in composition. In both, evergreens slicing into the frame from the upper left and coming in from the right on the other side of the river channel our focus onto the central subject of the rock formation. Made in opposite seasons, the atmospheric effects and the subject they frame have opposite values in the two images. In winter, the whiteness of the snow coating the trees and, on the right, drifting through the air, frame the darker surface of the of stone. In summer, the trees are silhouetted in shadow, as is the rock face itself on the right,so that light and dark are reversed. El Capitan emerges brightly from the shadows instead of retreating darkly from the snow.

The two photographs of El Capitan were made at or close to ground level. But Half Dome is a subject that, being far loftier and farther away, is seen from a much higher vantage point. The season is again winter, as we can see from the snow dusting the top of Half Dome and lying on the valley below. And again, the view is focused on the rock face by shadows coming in diagonally in the foreground on the left and in the distance on the right, where they fall on the rock face itself. The blocking of the image – Adams’ strategy with these shadows – is the same as in the undated view of El Capitan. But the shape of the shadow on the right isn’t geometrically abstract, as if it were a hypotenuse, this time. Instead, it has the almost cartoonish shape of a giant’s boot pressing down on the valley floor.It is a subconscious metaphor for Half Dome itself.

It is this sort of genius for implicit structure that will keep Adams’ work alive and ultimately give it a kind of durability – an innate timelessness – that lasts for the ages. As he himself aged, he turned his dramatic aesthetic on more humble subjects found at ground level, as we see in the two latest prints in the exhibition, “Aspens Horizontal” and “Aspens Vert II,” both made in 1958. Here too his ability to dramatize his subject by pulling it out from a dark background abides. Because the subject is a commonplace one, Adams’ aesthetic is perhaps even more powerful in these more mellow, late images.

Before moving to Los Angeles, Colin Westerbeck was a Curator of Photography at the Art Institute of Chicago from 1986 through 2003. Since then he has written a weekly column on photography for the Los Angeles Times in 2006 and 2007 and has contributed frequently to Art in America. He has also taught photographic history on the under-graduate and graduate levels at the University of California, Los Angeles, and the University of Southern California from 2004 to 2008, and again in 2017. From 2008 until 2012, he was Director of the California Museum of Photography at the University of California, Riverside. His most recent books are Chuck Close: Photographer (Prestel, 2014), A Democracy of Imagery (Steidl, 2016), and a completely revised and up-dated edition of his 1994 book co-authored by Joel Meyerowitz, Bystander, A History of Street Photography, published by Laurence King in 2017. In 2018, Harper Collins published his Vivian Maier: The 35-Millimete Color Photography.