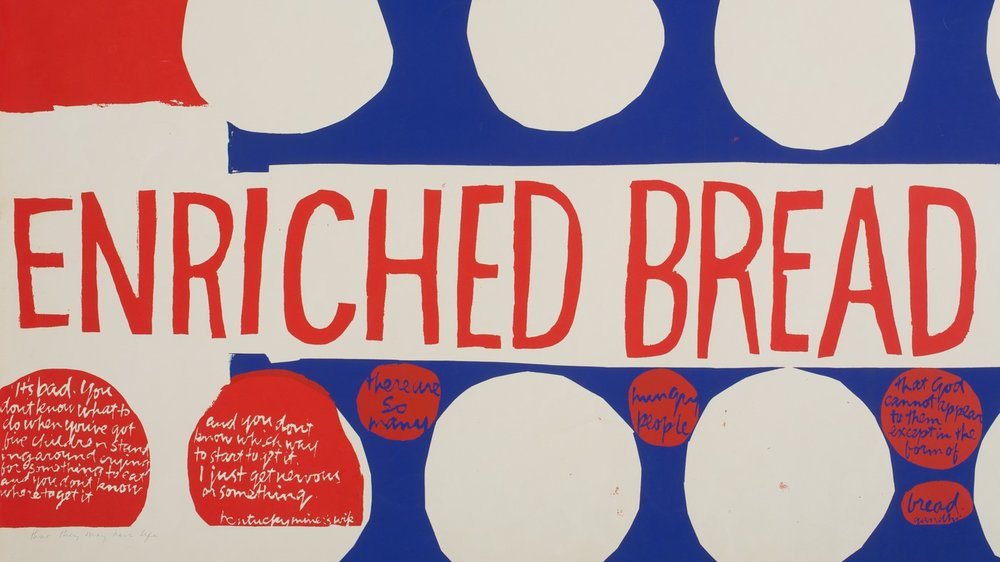

Corita Kent, that they may have life, 1964, serigraph

Courtesy of the Corita Kent Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community, Los Angeles, CA

Corita Kent: Transubstantial Matter

BY JOEL KUENNEN

Sister Mary Corita worked miracles. She turned ads into Art.

"It's bad. You don't know what to do when you've got five children standing around crying for something to eat and you don't know where to get it and you don't know which way to start to get it. I just get nervous or something."

This quote adorns two red dots on Sister Mary Corita’s 1964 work that they may have life. Scrawled across the middle of the work in large red letters is “ENRICHED BREAD”. The graphical motif of the work recalls the American flag and the design of Wonder Bread packaging. Wonder Bread is itself a bit of wonder. Early in the industrialization of bread production, people could no longer live off bread alone. The vitamin load that made bread a millennia-old staple of human beings had been processed out. The solution was to enrich the bleach-white loaves with vitamins, a government sponsored initiative during WWII rationing known as the “Quiet Miracle”. Wonder Bread could again sustain life. Plus, it was already sliced! This conjugation of symbols ripped from advertising contextualized with a heartfelt yearning for a just world epitomizes Corita’s practice.

The concept of transubstantiation within Catholic tradition holds that during the Mass, the bread and wine offered is transformed through the sacrament of the Eucharist into the body and blood of Jesus. This transformation of essence, not to be confused with symbolic transposition, is an artistically revolutionary activity and one that shares some commonality with the appropriative practices of Pop Art. This technique of taking something up and transforming it into something else with different messages and possibilities allows the freedom to critique and transform in the same act. However, Sister Mary Corita was not your average Pop artist.

Corita Kent, or Sister Mary Corita as she was known before she left the Order of the Immaculate Heart, was born in 1918 in Fort Dodge, Iowa. At the age of 18, she joined the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Los Angeles, a teaching order originally founded in Spain with the goal to improve the educational prospects of young women as a means to benefit society. Kent took classes at Otis and Chouinard Institute of Art, going on to receive her MA from USC in Art History. Kent became well known as a teacher and chair of the Arts Department at Immaculate Heart College. Her classes were visited by Alfred Hitchcock, Saul Bass, and Buckminster Fuller and she entertained friendships with John Cage and the Eames brothers. Ed Ruscha would send his students to Kent’s openings. Kent, notes Art Historian Susan Dackerman, attended Andy Warhol’s 1962 opening at Ferus Gallery, the first time his soup can prints were shown in L.A..

That same year, as Pop Art looked critically upon a flattening, image-based culture, Kent and her religion were beginning to look critically at their own image. 1962 saw the formal opening of Vatican II, an ecumenical council convened to modernize the Catholic Church. Vatican II took on issues of representation, communication, and ultimately the role of the Church itself. Within this dogmatic unraveling, a rarity in the life of the Church, grew a healthy optimism for the social teachings of the Catholic Church to guide its reformation. Many hoped the Church would not only reform their exclusionary and baroque rituals but come to embrace its congregants and give them a chance to incorporate the Church into their modern lives. American Catholics hoped for the advent of female clergy, the ability for priests to marry, a reorientation of the Church’s energies around poverty alleviation and an end to its obscenely wealthy appearance. The Church needed to modernize to stay alive.

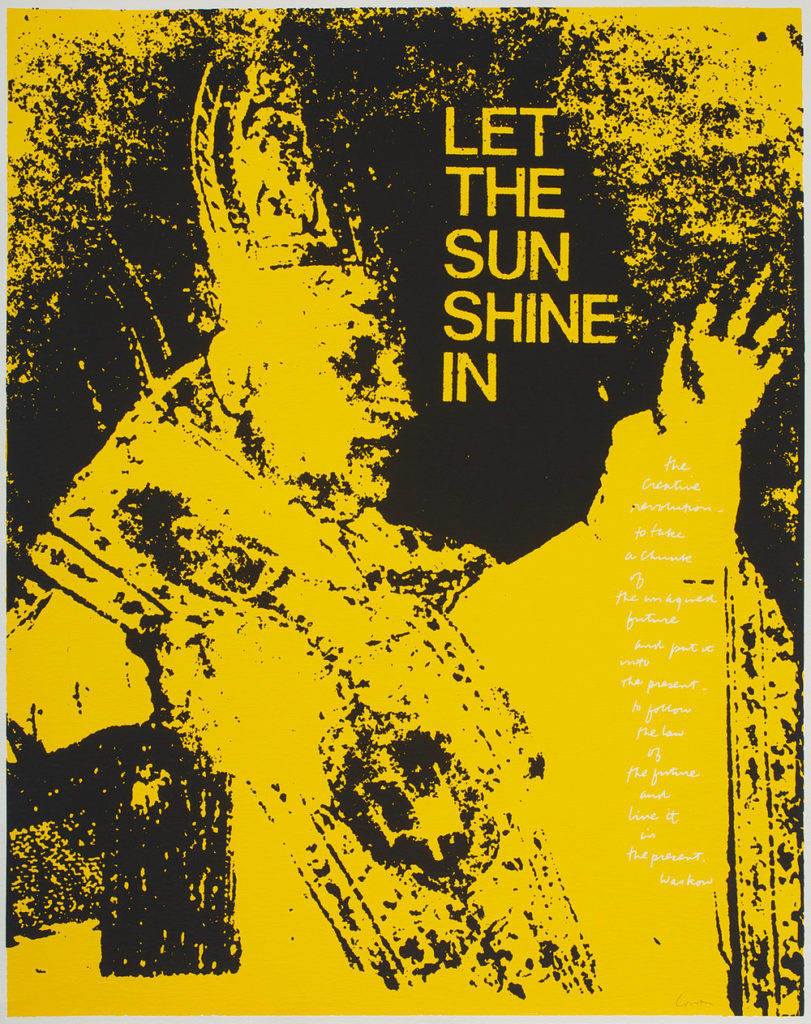

Corita Kent, let the sun shine in, 1968, Serigraph

Courtesy of the Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community, Los Angeles, CA

Pope Paul VI’s 1965, Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World Gaudium Et Spes, puts this grappling with a new world order front and center:

PROFOUND AND RAPID CHANGES ARE SPREADING BY DEGREES AROUND THE WHOLE WORLD. TRIGGERED BY THE INTELLIGENCE AND CREATIVE ENERGIES OF MAN, THESE CHANGES RECOIL UPON HIM, UPON HIS DECISIONS AND DESIRES, BOTH INDIVIDUAL AND COLLECTIVE, AND UPON HIS MANNER OF THINKING AND ACTING WITH RESPECT TO THINGS AND TO PEOPLE.

NEVER HAS THE HUMAN RACE ENJOYED SUCH AN ABUNDANCE OF WEALTH, RESOURCES AND ECONOMIC POWER, AND YET A HUGE PROPORTION OF THE WORLDS[SIC] CITIZENS ARE STILL TORMENTED BY HUNGER AND POVERTY, WHILE COUNTLESS NUMBERS SUFFER FROM TOTAL ILLITERACY.

Vatican II would bring about great changes to the liturgy (such as Mass in native languages and congregant-facing clergy), while other modernizations failed to come to fruition. Priests still could not marry, the curia (Vatican administration) retained much of its power and women remained relegated to gender-specific religious orders. However, social teachings, or the social justice current of modern Catholicism, became central to many religious orders in the United States. The Church, once the bank, community center, hospital and undertaker of the American frontier was beginning to confront the necessities of the urban environment within consumer capitalism.

The recoiling changes of the modern landscape created a society alienated and dispossessed amongst a sprawling shroud of fetishized signifiers. Visual culture had entered a golden age. In his book The First Pop Age, Hal Foster remarks “the conflation of fetishisms…was…a function of a consumerist economy in the postwar period in which the actual production of commodities was evermore obscured and our libidinal investment in them evermore intense.”[1] The spiritual animus of human beings was turning towards the product, the object and the image. Sister Mary Corita took a novel approach to criticizing this characteristic of modernity. Taking cues from the visual language of advertising, Corita began to insert the profound rather than merely causing an image to recoil upon itself.

In their recent book, Hippie Modernism, published in conjunction with The Walker Art Center’s eponymous 2015 exhibition, Lorraine Wild and David Karwan state, “Kent… took the language of commercial consumerism and transformed it into a vibrant picture of spiritual hunger and yearning for love and peace.”[2] Kent, unlike her Pop Art contemporaries, saw an opportunity to imbue the graphic landscape with exactly what it was missing — heart.

Warhol, on the other hand, could be said to do little more than show the image back to itself, thereby betraying its vacuous nature. What remains intriguing about Kent now is her sincerity. Whereas Warhol entered into entertainment and transcended into image himself, Kent kept her activist core and set justice at the center of her work, imploring her viewers to not forget that we are all in this together.

From 1965-1968, Corita’s work would become more and more political, reflecting a popular frustration with the Vietnam War and consumer capitalism as well as a profound desire to find a life worth living. The political landscape of the United States and her engagement with it would put her at odds with the Church as resistance materialized to the modernization efforts of Vatican II. The male clergy who maintained power after Vatican II were beginning to clamp down on the female religious orders who they viewed as taking liberties with the modernization edicts of Vatican II. In 1965, there were 180,000 Religious sisters in the United States. Over the next decade, that number would drop to 135,000.[1] Generally, this can be attributed to a decrease in the religiosity of the general public as well as an increase in the standard of living. However, this only accounts for the decline in new members. Many sisters chose to leave their orders, citing a frustration with the lack of true reform after Vatican II.

By 1968, Sister Mary Corita was gaining a level of celebrity and maintaining an exhaustive schedule. She decided to take a sabbatical, intending to return the following year according to those close to her. However, at some point she decided to leave the order and sought a dispensation from the Bishop to do so. She moved to Boston and continued to work. Two years later, the order of the Immaculate Heart of Mary reformed as a lay community, leaving the church en masse. Kent maintained close ties to the community and would bequeath much of her estate to the Immaculate Heart Community when she passed away in 1986.

Corita Kent’s work is often held up as a curiosity — the nun that made Pop Art, being a common moniker. But Kent’s work was doing something wholly different. While Pop artists like Warhol, Lichtenstein, Ruscha and Hamilton were cynically turning America’s images upon themselves, stripping them of their intended meaning and thereby making the image an object, Kent saw another option. Is an image not meant to convey? Is it not a vessel? Can it not sustain us? Might it only need to be enriched to once again become the bread of life?

JOEL KUENNEN IS THE CHIEF OPERATIONS OFFICER AND A SENIOR EDITOR AT ARTSLANT.COM. HE RECEIVED HIS MA IN VISUAL AND CRITICAL STUDIES AT THE SCHOOL OF THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO IN 2010. HE HAS PUBLISHED CRITICISM IN AMERICA AND THE UK AND WAS SELECTED TO PARTICIPATE IN THE 2012 ARTS WRITERS GRANT WORKSHOP WITH WALTER ROBINSON. HE WAS A CONTRIBUTOR AND AN EDITOR OF THE CONTEMPORARY VISUAL STUDIES READER WHICH WAS PUBLISHED BY ROUTLEDGE IN 2012. HE IS ON THE ORGANIZING COMMITTEE FOR THE SAIC IN NYC ALUMNI GROUP AND IS AN AMBITIOUS GARDENER. HIS CURRENT RESEARCH INTERESTS ARE CENTERED AROUND DIGITAL SELVES, THE INTERSECTION OF POLITICS AND CULTURAL PRODUCTION, AND ONLINE ART COMMUNITIES.

(1) Hal Foster, The First Pop Age, Princeton University Press, 2012. P. 25.

(2) Lorraine Wild and David Karwan, Agency and Urgency, Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia, Walker Art Center, 2015. P. 48.

(3) Center For Applied Research in the Apostolate. Retrieved 01/09/2017. http://cara.georgetown.edu/frequently-requested-church-statistics/